When the words attachment and teaching are used in the same sentence, a whole array of reactions tend to occur. While some of these reactions are positive, many teachers become quite defensive. Some of their arguments are listed below:

- Teachers already have so much to worry about and do, attachment is just one more responsibility unjustly given to teachers;

- Teachers are not meant to do the parents’ job;

- Teachers aren’t therapists;

- Teachers need to maintain a professional distance from the students in order to protect themselves from accusations of abuse.

I don’t really get the last one. To me, denying a crying child a hug is abuse in the form of neglect. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

These arguments demonstrate how overworked and stressed teachers are. They are afraid that more responsibilities will be thrown at them – and they have a point, it does tend to happen on a daily basis – and they will be under even more pressure. The application of attachment theory in the classroom, however, is not meant to make teachers’ lives more difficult; it is meant to make things easier.

Yes, you read it right. Easier. As an EFL (English as a foreign language) teacher I find these arguments a bit strange, not for lack of empathy for the teacher, but because language teachers have been applying attachment friendly methods for decades without much fuss. We have learned, from research, that they are very effective when teaching a foreign language, rather than traditional teacher centred methods. Therefore, we implemented them, made them the norm and have had very positive results. I wonder if it would be more difficult to do the same with other subjects.

To explore this crazy idea, I’ll try to answer these three questions in the next lines:

- What the hell is attachment, anyway???

- Why is it relevant to teachers?

- How can we make attachment aware teaching possible… and enjoyable… and easy?

Attachment

According to John Bowlby – the guy who made attachment a thing – attachment is:

“Proximity-seeking to the attachment figure in the face of threat, due to the capacity to sense conditions that could be dangerous: being alone, unfamiliarity, rapid approach”.

Got it? No? Me neither. I needed a better explanation and I understood attachment for the first time during a training session with Suzanne Zeedyk.

Click here to watch one of her lectures.

Click here to access her blog.

Zeedyk has a less orthodox way of explaining attachment: she talks about sabre-toothed tigers and teddy bears. Imagine prehistoric human beings using their instincts to survive from predators. If a sabre-toothed tiger attacked the group, it would likely go for the weakest, easiest prey: the babies. The babies can`t protect themselves or run away, but their parents can do that for them. While adults have the instinct of running for their lives, babies have the instinct of getting the adult`s attention so they don`t get left behind. Babies cry and scream because they don`t want to be left alone, they want to be held and kept close. This attachment is key to their survival, so it`s the most fundamental part of their nature. When they don`t have that, all that`s left is fear – which can mean trauma, anxiety and a range of emotional issues.

To make it clear, Zeedyk describes an internal teddy bear. A child uses a teddy for comfort, and little by little they develop their own internal teddy bears they turn to for comfort in moments of distress; that`s them building resilience. But this can only happen properly if they had this comfort in their early childhood provided by their parents (or whatever caring figures they had) in the form of attachment.

If teddy bears are the antidote to sabre tooth tiger fear, how do we build our internal teddy bears? Is it only with the help of parents or primary care-givers? If we don’t develop during our early years, is it possible to fix it? The answer to these questions is in how our brains work, which also answers the question on why this is relevant for teachers.

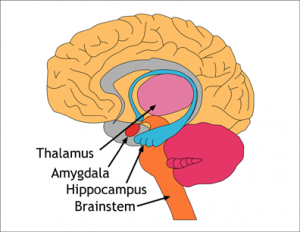

Brains

I must stress at this point, that even though I am passionate about psychology, I’m not a neuroscientist and the explanations below are rather simple. I have asked experts to check them, though, and they said it isn’t wrong, so let’s do this!

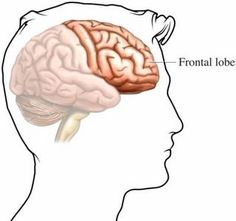

This is your internal teddy bear, your frontal lobe:

Not as cuddly as one might have thought, but it works wonders. The frontal lobe is, among other things, responsible for our ability to:

- learn, reflect and concentrate;

- plan and problem solve;

- manage stress;

- control impulse;

- regulate emotions.

As you probably gathered, our students’ frontal lobes are very important to us teachers. If they are not functioning properly, students fail to learn. They also fail to behave, which is not helpful and it makes our lives much harder.

According to Margot Sunderland, author of The Science of Parenting (2015), this part of the brain is not fully developed when we are born, we need to learn how to use it.

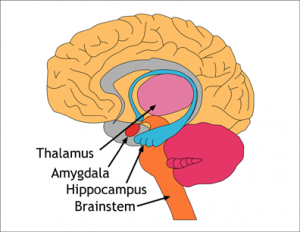

Our lower brain, however, is fully functional and very much online from birth.

This part is responsible for (again, among other things we don’t need to focus on now):

- hormonal forces;

- emotional systems;

- fight or flight reaction.

This is why when a toddler is hungry they might throw themselves on the floor crying and screaming and have a distress tantrum. They don’t have a fully developed frontal lobe to warn them: food will probably come soon, your mum always makes lunch at twelve; why don’t you play for twenty more minutes and then go check if it’s ready. As adults, with a well-developed frontal lobe, when we feel hungry we tend to keep calm and go make ourselves a sandwich.

The development of the frontal lobe is deeply connected to the way the lower brain is activated. It has 7 hormonal systems at work:

- CARE

- SEEKING

- PLAY

- RAGE

- FEAR

- PANIC/GRIEF

- LUST

LUST is related to sexual behaviour, so we’ll ignore it for now. Let’s talk about the other six:

CARE RAGE

SEEKING FEAR

PLAY PANIC/GRIEF

The ones on the left are pro-social hormonal systems and the ones on the right are alarm systems. Different situations may activate one or more of these systems, which function like muscles. The more they are activated, the stronger they become. Growing up with the alarm systems being frequently activated by a certain parenting style, or more severely by abuse and trauma, the child may become an adult with these systems very much present in their lives.

To use Sunderland’s example, it’s like a faulty car alarm that goes off for any reason. If you work for customer service, you might have noticed how this situation is very common. Because the alarm systems were constantly activated throughout most of this person’s life, they compromised the development of the frontal lobe. Louis Cozolino, author of The Social Neuroscience of Education (2013), explains that:

“Nonloving behavior signals to the child that the world is a dangerous place and warns him or her not to explore, take chances, or trust others. It also teaches him or her not to trust the information others are trying to convey”.

What these alarm hormonal systems are basically saying is: you are in danger, there is a sabre tooth tiger around, you need to either run or fight it. There is no time to learn, no time to regulate emotions, you need to act or you’ll die. Many adults and children often get aggressive or withdrawn in the presence of a problem; they tend to calm down when somebody comes to their aid. Babies, who can’t fight or run, cry. When an adult picks them up and calms them down, the CARE system is activated and they feel safe.

The pro-social hormonal systems are key for the development of the frontal lobe. The more they are activated, the more we make positive connections in the frontal lobe. When we feel safe, loved and are surrounded by people who make us laugh, our brains are at ease and ready to learn. If a child or adult doesn’t feel safe in the classroom, they will have a much harder time learning.

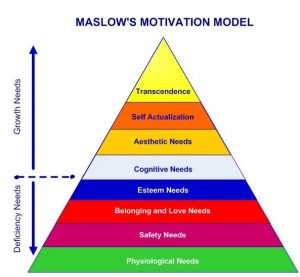

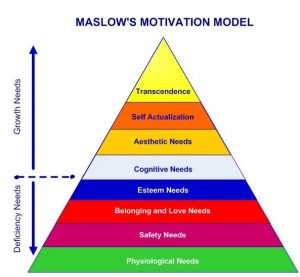

Here’s a model of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs:

When it comes to learning, it is believed that the deficiency needs should be met in order for the growth needs, or learning, to come about optimally. However, I dare say that “feeling safe”, or shall we say, attachment needs, should be at the bottom of the pyramid, along with basic physiological needs, such as water and food. In fact, feeling safe is more important for learning than actually being safe. I’ll tell you why.

A very sad experiment conducted in the 1950’s by Harry Harlow – to be fair, it wouldn’t pass an ethics committee nowadays, but since we have the data, let’s use it – analysed the behaviour of new-born monkeys when offered two types of inanimate surrogate mothers: a cuddly cloth one and a wire one. Both surrogates provided milk for the monkeys’ nourishment.

All monkeys preferred the cuddly one, even when they didn’t offer any milk. In one of the variations of these experiments, the monkeys were divided into two groups and offered either the cloth or the wire mother. The monkeys with the cloth ones survived longer than the ones with the wire ones, even after the milk was removed from the cuddly ones.

The saddest part is that Harlow didn’t really need to conduct this mean experiment. We had empirical evidence from UK orphanages in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. In reaction to the appalling death rate among the children, and thinking it was the result of the spread of germs, doctors recommended contact among children and with the staff should be kept to a minimum. That made the death rate rise even more. It only decreased when physical contact and nurturing was encouraged.

Authors such as Louis Cozolino and Jeremy Rifkin, who wrote Empathic Civilization (2009), defend that nurturing, or attachment needs, are at least as important as water and food for human survival. Hence why we also need them met for learning to occur.

Applying attachment theory in the classroom

Now, to the practicalities. How can we activate those pro-social hormonal systems in our students’ brains to help them learn? Here are some things we do NOT need to do:

- Be the students’ parent;

- Be the students’ therapist;

Here are some things we could do:

- Listen to students and let them have say on how to make the classroom environment as comfortable as possible so that they feel safe there;

- Have empathy and treat them with compassion;

- Prepare attachment friendly lessons.

By attachment friendly lessons I mean those who activate the CARE, SEEKING and PLAY systems of the brain and avoid the alarm systems. Cozolino has a few suggestions:

Play

As pointed out by Cozolino, Research shows that “play enhances sensorimotor development, social-emotional skills, abstract thinking, problem solving, and academic achievement” (2013). Jokes, games and any fun activities will help students learn, no matter the subject. That includes adults!

I appreciate that the concept of fun may be different for children and adults. Getting to know your students and what they enjoy is very helpful. In my practice as an EFL teacher, I like to use quiz show style games for the boring grammar activities. They are the same activities, but the fact I turned them into a competition between two or three groups makes it a lot more interesting.

Some of my peers have shared a lot of interesting games for learning and recycling vocabulary, which go from simple pick a word and give hints so the rest of the group can guess what the word is, to a twister mat with words stuck to the spots. Kahoot.com and jeopardy games go a long way using technology and fun to review materials. Role-plays are also fun and help develop a number of skills.

Just by making students walk around the room and physically move during an activity you’ll be activating their PLAY and SEEKING systems. By making activities as social as possible, like group and pair work, you’ll be also activating the CARE system.

Exploration

When students are curious and have an urge to learn more, discover and explore, they SEEKING system is being activated. In class, I sometimes have students find the answers to a question by looking for them on the walls or under their chairs, etc. A little blu-tak can help with that. I also like to take my students out of the classroom to have a lesson somewhere more stimulating, such as a museum or a park. A stimulating classroom, with things for students to look at and resources for them to use can also be very good for the SEEKING system.

Exploration is great not only for learning but also for health. “The effects of environmental stimulation on brain growth are so robust that they even counteract the effects of malnutrition” (Bhide & Bedi, 1982 apud Cozolino, 2013). When a student is curious about something, don’t dismiss them and, instead, give them the tools to find out more.

Story-telling

Story-telling can be used in two ways: the teacher using a story to teach something and the students sharing their own stories. Stories help organize neural integration, which means your brain cells form new connections, connecting different pieces of information to enhance knowledge. Our brains also have unlimited storage for stories and songs. Whatever is taught through them is more likely to remain in long term memory.

When students share their own stories or simply write them down, this helps them regulate their emotions, which is great for their frontal lobe development. Putting feelings into words also boosts immunological health (it’s actually shown to increase T-helper response!) and lowers heart rate. Sharing their own experiences helps students calm down and feel like they belong, activating the CARE system, especially if classmates are listening and reacting positively.

Student Autonomy

Teachers have their own biases and judgements. We can’t help it, our brains are programmed to have them. By taking a step back and giving students autonomy in their own learning, we expose them less to these biases.

One of Albert Bandura’s contributions to the study of education psychology is the self-efficacy theory, whereby he defends that one’s expectations for themselves can influence their own performance. Therefore, people may think in a self-sustaining (optimistic) or self-debilitating way, which could affect their performance positively or negatively, respectively. Because of the social nature of humans, society can widely influence our expectations of ourselves and other people.

Therefore, when a teacher has low expectations for students they see as weak or less talented, they tend to live up to those expectations. Teachers can inflict such an influence because of our position of authority. Students tend to look up to and trust their teachers (which is great, otherwise they wouldn’t learn from them), so our impressions, even when not explicitly expressed, will have a powerful impact on the pupils. Their classmates, even though they can still affect how students feel, won’t have such a powerful impact.

Peer teaching can be a great way to avoid that exposure. When we supply different students with pieces of information and have them teach each other, we are activating their CARE system by showing we trust them. It is also a very social activity, which is always positive.

In EFL we recommend a reduction of TTT (teacher talking time) as a way to make the lesson more student-centred and give them a chance to learn from each other. In this method, the teacher is there to give students the tools to learn by themselves cooperatively rather than transfer knowledge.

Teacher well-being

Last, but not least, teachers need to also be feeling safe in order to teach effectively. Cozolino explains that “when a teacher is harsh, critical, dismissive, demoralized, or overly stressed, their students attune to and come to embody these antilearning states of brain and mind” (2013). Both teachers and managers have a role in maintaining the staff’s well-being.

If we carry on using the attachment approach for management, the principles are the same. How do we activate the pro-social systems in teachers? I have a few ideas:

- CARE – being listened to (but like, really!), belonging, having a say, participation on decision making, no micro-managing, mutual trust between staff and management, teacher autonomy…

- SEEKING – professional development, training sessions, trying new methods and new activities, sharing materials, peer observations…

- PLAY – staff socials, dynamic work environment, encouragement to create fun lessons, places to relax…

The ellipses are there to emphasise there are many other things which can be done, these are just a few suggestions.

Depending on where you work, some of these might sound obvious, but they are still rare in UK companies. For teachers – as well as other professionals – to remain motivated, they need to feel they are working together for a greater good rather than for financial reward (for themselves or the company). “The beneficial effects of this approach on productivity, efficiency and morale are well documented by experiments in factories, but whether through complacency or ignorance are largely ignored by British managers” (Sutherland, 2013).

It does not mean that teachers can be underpaid and still be happy and chirpy. We still need to get paid enough so we don’t have to worry about money. Once that is out of the way and we have our other deficiency needs met, including the attachment ones, then we are ready to live up to our potential and continue to develop in our career. Happy teacher, happy students.

References:

- Aubrey, K. and Riley, A. (2016). Understanding and Using Educational Theories. London: Sage.

- Cozolino, L. (2013). The Social Neuroscience of Education. New York: Norton.

- Cozolino, L. (2014). Attachment-Based Teaching. New York: Norton.

- Illeris, K. (2009). Contemporary Theories of Learning. New York: Routhledge.

- Mooney, C. G. (2010). Theories of Attachment. St. Paul: Redleaf Press.

- Pierson, R. (2013). Every Kid Needs a Champion. Video recording, YouTube, viewed 01 Oct, 2017, < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFnMTHhKdkw>

- Positive Psychology Program (2016). Albert Bandura: Self-efficacy for Agentic Positive Psychology. [online] Available at: https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/bandura-self-efficacy [Accessed 01 Oct. 2017]

- Rifkin, J. (2009). The Empathic Civilization. New York: Penguin.

- Sunderland, M. (2016). The Science of Parenting. 2nd New York: DK.

- Sutherland, S. (2013). Irrationality. 2nd London: Pinter and Martin.

- Zeedyk, S. (2015). Sabre Tooth Tigers &Teddy Bears. Video recording, YouTube, viewed 21 Feb, 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zsAV_qez7SE&t=5932s>

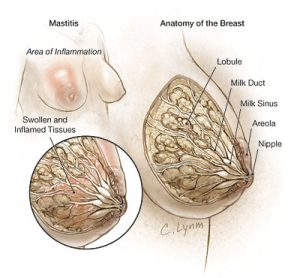

Talking to a group of teachers the other day, we agreed how interactive boards were an amazing resource in the classroom. I mean, who needs flashcards when you have Google Images? Googling visual aid for students, however, can be a tricky business. Especially if you are an EFL (English as a foreign language) teacher like me, and might use this resource quite often, increasing the chances of checking out seemingly innocent words just to realise they have an obscene side. Google is always improving its filters, but sometimes even Safe Search filter fails to prevent students from becoming traumatized or teachers from having an extremely embarrassing experience.

Talking to a group of teachers the other day, we agreed how interactive boards were an amazing resource in the classroom. I mean, who needs flashcards when you have Google Images? Googling visual aid for students, however, can be a tricky business. Especially if you are an EFL (English as a foreign language) teacher like me, and might use this resource quite often, increasing the chances of checking out seemingly innocent words just to realise they have an obscene side. Google is always improving its filters, but sometimes even Safe Search filter fails to prevent students from becoming traumatized or teachers from having an extremely embarrassing experience.