Hey there, my name is Susan, and a lot of people hate me. They are very concerned with my impact on their country`s economy, and that I might be abusing the system. They believe I should be sent back to my country of origin and only come back if I have the skills they need. I`m an immigrant on benefits in the UK.

Hey there, my name is Susan, and a lot of people hate me. They are very concerned with my impact on their country`s economy, and that I might be abusing the system. They believe I should be sent back to my country of origin and only come back if I have the skills they need. I`m an immigrant on benefits in the UK.

Let me clarify something, though: I do work. I just don’t make enough money to support my family, and I’m a single mother, so I get help from the government. I’m very grateful I am having the opportunity to live in a house that’s big enough for me and my family, that I don’t struggle to buy food, that my son can go to childcare while I work, that I get to spend time with him, too. I didn’t want to be in a situation where I need benefits and I’m working my way out of it so I won’t need help in the future. However, being in this situation was out of my control, so I’m glad I had this option. Others aren’t so happy about it.

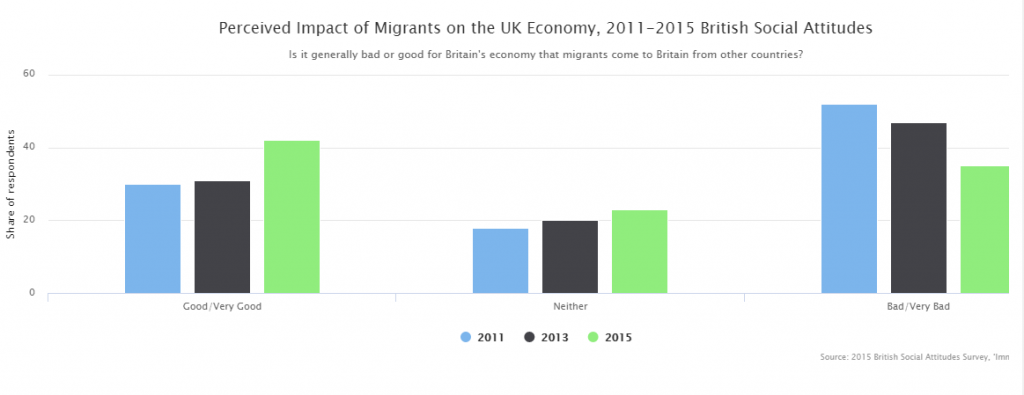

According to a 2013 survey, more than half the British population believes that the cost of having immigrants outweighs the benefits. A lot of people are concerned about the “benefit tourists” and immigration is perceived as one of the most important issues the UK faces. This is one of the main reasons Brexit is happening, so this perception is causing major changes in the UK policy and may have a huge impact in its economy and politics.

Don’t get me wrong, I have never been mistreated and nobody has ever been rude to me or told me I should leave. In fact, when I catch people making negative comments on immigration and I remind them I’m an immigrant myself, I often hear: “But I don’t see you as an immigrant”, or “You’re not the problem”. The problematic immigrant is not usually the one close to you, it’s this distant image of an ill-intentioned, strange looking guy, speaking another language and taking advantage of anything he can. I don’t look like that guy. Personally, I don’t know anyone who looks like that guy. Most people don’t.

The Migration Observatory points out that “In something of a paradox, while vast majorities view migration as harmful to Britain, few claim that their own neighbourhood is having problems due to migrants”. Surveys show that a minority of the British population think the nearby migrants are the problem. In fact, the most contact people have with immigrants, the more positive is their view of them. It might seem a lot when we say that, in 2013, more than half of Britain believed there were too many immigrants in the country; but in 1970, about 90% of people had this view. The number of people who have this negative view of immigrants have been steadily decreasing since then, as the presence of foreigners increases.

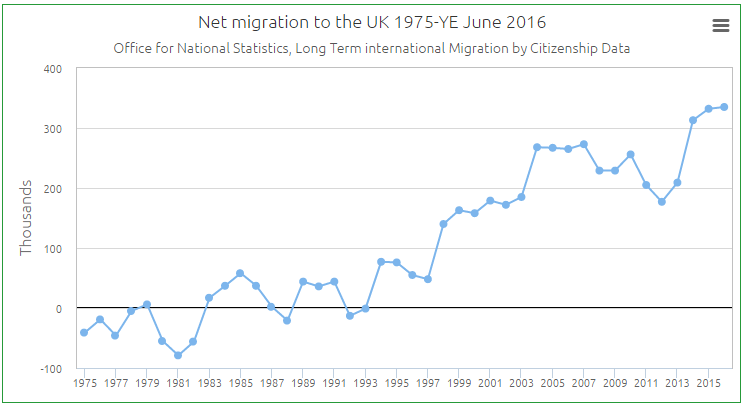

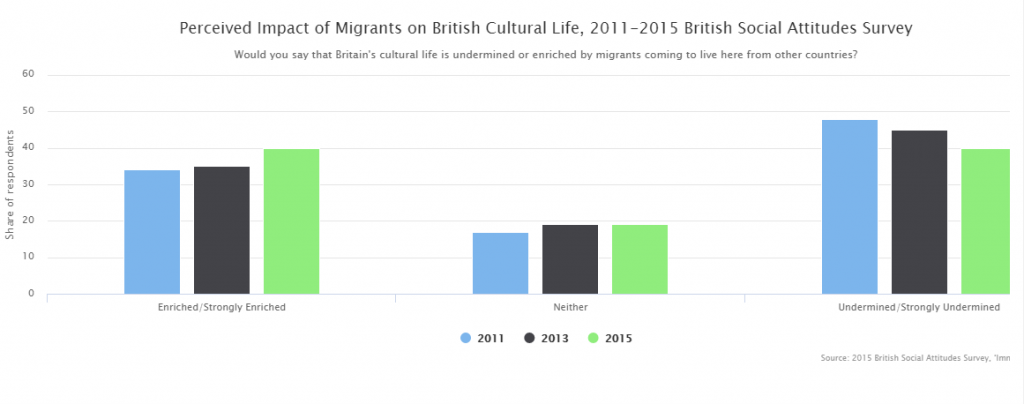

There has been a spark in migrations to the UK since 2013, with a rapid increase of people arriving from a variety of countries. How did that affect the public impressions of foreigners? Positively! Though most people still believe immigrants have a negative impact on the economy and cultural life in Britain, this is slowly changing:

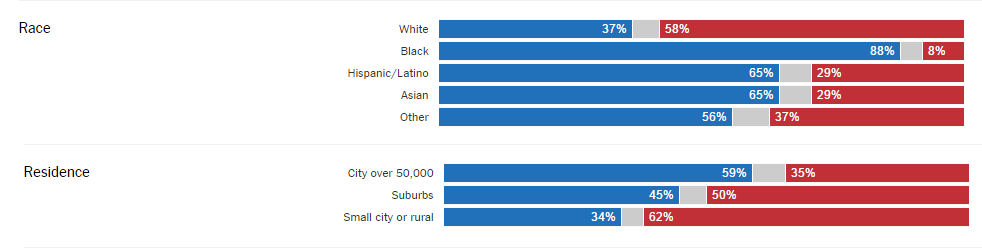

Similarly, in the US, the voters who most supported Trump, who based his campaign largely on the “immigration problem”, were the least likely to have contact with immigrants: the people living in small towns. Most of the big cities and areas with a multicultural environment, had less people vote for Trump, according to the exit polls (red is votes for Trump and blue is votes for Hillary):

It seems that, getting to know immigrants may actually change your view of them (really!). When you get to know them, you might realise they are not very different from you at all. Maybe the reasons why they came to the UK are actually something you’d do, if you were in their position. The UK is actually one of the countries where most nationals emigrate, with 8% of its citizens living in another country.

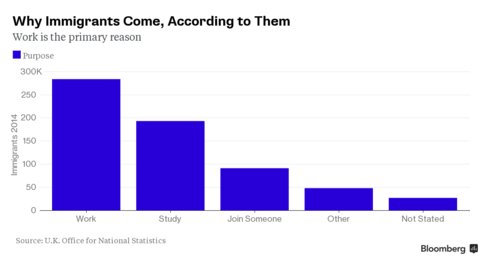

Why do people come to the UK?

Most people come here to work. The second favourite reason is to study and the third is to join someone, like a spouse. Moving countries is not easy and I had different reasons to do so. I think nobody moves to a different place for one reason only. I had to make huge sacrifices to be able to move here and it wasn’t a decision taken lightly.

I was married to an Englishman and we lived in Brazil for 5 years. He started missing home and his family a lot, so we decided to make plans for a move to the UK. That was 2014, I was in my last year in University and didn’t want to rush out of the country. My graduation research was going to be published into a book and I wanted to take care of all that before I left.

A couple of things changed our plans completely, they happened sort of at the same time. Brazil was entering a political and economic crisis, a lot of companies downsized, including the one my husband worked for and he was one of the many employees who were laid off. I then discovered I was pregnant. We lost our health insurance and were both working as freelance teachers, so there were a lot of uncertainties in our minds. We decided it would be best to move to the UK earlier than we had planned.

It wasn’t easy. We saved money, sold furniture and electronics, our car, gave lots of stuff away. Because the currency suffered a huge drop with the political crisis, our money wasn’t much when we arrived in the UK. We weren’t entitled to benefits (it’s not as easy as you think) so my husband had to find a job quickly. I wasn’t there for my book launch, I couldn’t attend any of the events I was invited to lecture at, I made huge sacrifices in my career.

Why did I do all that? For my son. It was important to me that he would have access to healthcare, to a good education, that he would be safe and that I’d be around to raise him instead of working ten hours a day like I was doing in Brazil. The UK is an attractive destination for migrants because it offers these basic human rights to everyone. In most parts of the world, basic human rights are a luxury.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I love Brazil and I miss it a lot. I often think about going back. I miss the social life, the weather and the friendly, happy people. But then I remember the stress and my son doesn’t deserve it. No one deserves it, but most don’t have a choice.

What do I mean about stress? Well, I noticed how stressed I was when I travelled to California in February, 2014. The day I arrived, a friend picked me up from the airport and parked outside a restaurant to pick up a takeaway and told me to wait in the car. As I waited, I didn’t relax. I kept looking at the review mirrors looking for a person or a motorcycle approaching the car. I was afraid of being robbed or kidnapped; it took me a few minutes to realise I was being silly, it wasn’t going to happen there. I was in California for a few weeks and the feeling of being able to relax a little for the first time in years is hard to describe.

I used to drive to work in Sao Paulo, the largest city in Brazil and there was a lot of traffic. While I was stuck in traffic, it was common to see a motorcyclist stop next to a car, take a gun out and ask the driver for money and valuables. There’s no escape, I was just sitting in my car wondering when it was going to be me. I would hide my bag under my seat and keep a fake wallet and phone near me, ready to give to the next criminal to approach me. It’s a risky move. If they realise you tricked them you might get shot. Luckily, though I’ve been physically attacked by muggers before, none of them had a gun. In fact, I was only held at gun point by police. What had I done wrong? Nothing. Where there’s a lot of violence and crime, the police tend to be more aggressive, too. It’s a snow ball.

Brazil has a high murder rate, worse than Iraq. A woman is raped in Brazil every 11 minutes. It has one of the worst wealth distribution. The government recently signed a decision to cut all investments in health and education for the next 20 years. I don’t want this for my son. If you are a parent, we probably have that in common.

Nowadays, I still sometimes hold my breath when I hear a motorcycle. When a stranger is walking towards me, I look at their hands, to see if they’re reaching for a gun or a knife. It’s only for a second, then I remember I’m not in Brazil and I relax. I can only begin to imagine what it’s like for a Syrian refugee when they have crossed the border and they hear an airplane. Imagine this: what does it feel like to feel panic, then realise it’s just a plane, not a Russian bomber? That’s an exercise we all need to do before we say no to refugees. Ask ourselves this kind of questions. What does it feel like when your one-year-old hears an airplane noise and says “bomb” before he’s even learned to say “dog”. What does it feel like for a ten-year-old refugee in Europe who doesn’t want to go to school because his school got bombed back in Syria and he saw his friends die?

I’m not saying all immigrants are good, all I’m saying is: get to know them. The odds are it’ll change your view on immigration.

But is immigration actually bad for the UK?

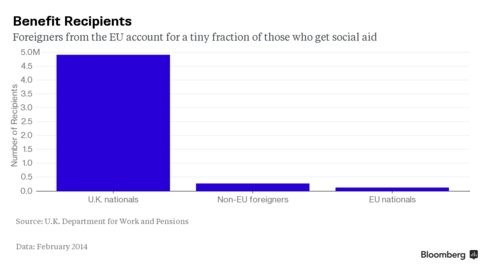

According to the Migrants and Citizens website, “there is no foundation for the claim that immigration is undermining the British welfare state. In fact, it looks like the opposite is true”. Almost 93% of benefits go to UK nationals:

The site further explains that:

“In fact, all the data points to the fact that the vast majority of EU migrants actually pay into the UK’s social security system without taking as much out. A 2009 UCL study, comparing net tax receipts with likely expenditure, suggested that Eastern European A8 migrants paid in 35% more than they were likely to receive in welfare services, while natives’ taxes were equivalent to only 80% of the money they received in benefits. These A8 migrants in the UK – are also 60% less likely than natives to receive state benefits or tax credits, and 58% less likely to live in social housing. Although different models of income and outgoings shifted the balance slightly in local citizens’ favour, the overall conclusion was clear: ‘A8 immigrants are unambiguously net fiscal contributors, while natives are unambiguously receiving more than they contribute’.These findings have since been confirmed by a follow-up study released late in 2014, which calculated that EU migrants who have arrived in Britain since 2000 have made a net fiscal contribution of £20bn (non-EU migrants’ net contribution over the same period was £5bn)”.

Basically, I’m the exception here. Most immigrants contribute more than they receive in the UK and I’m hoping to join them soon. Sending immigrants away may actually result in a cut on benefits and pensions for British citizens and less investment for the NHS, not the opposite.

My unrequested advice:

- If you are British, get to know foreigners, learn more about their countries and the situation around the world.

- If you are an immigrant, join groups that are working to inform and fighting for migrant’s rights in the UK. One Day Without Us and The 3 Million are examples.

- When feeling discriminated, try talking sensibly about how you feel and avoid accusing others of wrongdoing (unless it’s clearly a case for the police), they might not have noticed they’ve done something. Do talk about it, though.

- Empathy is underrated and should be exercised more often. Whether you are an immigrant or a UK national, try to imagine what it’s like to be in a different situation; try to understand the reason why people do the things they do.

- Be sceptical of politicians who blame immigrants for the country’s problems, this is the oldest trick for manipulation. Make sure you fact check all of their claims.