Para muitos de nós, é difícil compreender a recente eleição de Bolsonaro. As intensões de voto resultaram em fim de relacionamento, brigas de família, quebra de amizade. O Brasil era um país onde se evitava falar de política, onde os relacionamentos sociais eram mais importantes do que opinião ou até atos moralmente duvidosos. Tudo mudou. De repente, mudou. Eu escrevo isso, assistindo de uma considerável distância o que está acontecendo em meu país de origem. Do conforto da Inglaterra, onde a ameaça do Brexit agora não parece tão ruim, lhes ofereço a minha análise do que causou essa baderna irreversível; e a resposta é simples: o medo.

Para muitos de nós, é difícil compreender a recente eleição de Bolsonaro. As intensões de voto resultaram em fim de relacionamento, brigas de família, quebra de amizade. O Brasil era um país onde se evitava falar de política, onde os relacionamentos sociais eram mais importantes do que opinião ou até atos moralmente duvidosos. Tudo mudou. De repente, mudou. Eu escrevo isso, assistindo de uma considerável distância o que está acontecendo em meu país de origem. Do conforto da Inglaterra, onde a ameaça do Brexit agora não parece tão ruim, lhes ofereço a minha análise do que causou essa baderna irreversível; e a resposta é simples: o medo.

Parece um pouco simplista e exagerado, uma generalização de fenômenos muito mais complexos. Eu concordo – parece mesmo. Quando pensamos no medo, invocamos uma imagem de nossos corações acelerando, os joelhos tremendo, o suor de pânico escorrendo pelo rosto. O medo é muito mais do que isso e ele se manifesta de diversas formas. O medo pode vir de um objeto externo, como uma onça pintada se aproximando do seu acampamento; ou de uma reação interna, uma associação antiga entre um trauma de infância e um objeto tão inócuo quanto um sapo de brinquedo. O medo pode ser inato e instintivo, como a tendência do ser humano em temer cobras e aranhas, ou pode ser condicionado, como aquele arrepio na espinha quando ouvimos a música de suspense em um filme. Mais importante: o medo é potencializado por traumas.

Com alta criminalidade, corrupção, violência doméstica, altos índices de exclusão social, discriminação e impressionante disparidade na distribuição de riquezas, o Brasil é um país de traumatizados. Eu sou professora de inglês e tenho alunos de uma grande variedade de nacionalidades. Notei que, quando se fala em criminalidade, todo brasileiro tem pelo menos uma história de assalto. Eu gosto de observar os outros alunos escutando, estupefatos com a calma do estudante brasileiro ao descrever tal episódio de violência. Raramente um aluno de outra nacionalidade tem uma história dessas para contar, e eu incluo aqui colombianos, tailandeses, chineses e estudantes de diferentes países africanos. No Brasil, a violência é normal.

É impressionante como nos acostumamos com essa realidade. Eu morei nos Estados Unidos e, depois que voltei para o Brasil, passados alguns anos fui visitar amigos na Califórnia. Eu notei o quão estressada estava quando meu amigo, que havia me buscado no aeroporto, parou em um restaurante para buscar nossa janta e me disse para esperar no carro. Já estava escuro e eu ficava de olho no retrovisor para ver se alguém se aproximava. Durante cinco minutos eu estava em estado de alerta constante, olhando ao meu redor caso visse alguém suspeito. Quando ouvi uma motocicleta passar, prendi a respiração. Quando meu amigo voltou para o carro, eu me dei conta de onde estava e me lembrei de que não precisava me preocupar. Relaxei. As semanas seguintes foram como uma terapia. A distância daquele estresse todo me fez muito bem. Mas a hora de voltar para o Brasil chegou e eu voltei ao antigo stress, agora muito consciente dele. No mesmo ano engravidei e decidi me mudar do país.

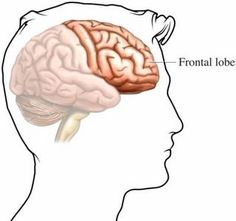

O que acontece quando todo esse stress não vai embora nunca? Quando estamos constantemente expostos à violência e nos sentimos desamparados? Essa é a parte importante, que nos ajuda a compreender o comportamento de nossos colegas eleitores. Precisamos falar do cérebro. Mais especificamente, a parte inferior do cérebro e o lobo frontal. Só para deixar bem claro, essa vai ser uma explicação bem por cima e simplificada, para haver um entendimento geral sobre como um comportamento ocorre. Não entrarei em detalhes neurocientíficos porque já tem nerdice demais como está.

Quando nascemos, o lobo frontal está offline. O lobo frontal se desenvolve conforme crescemos e não está funcionando muito bem até nos tornarmos adultos – às vezes nem depois disso. Essa é a parte do cérebro responsável pelo raciocínio lógico, pelo aprendizado, pela capacidade de controlarmos nossas emoções e comportamentos. Bebês não sabem fazer nada disso. Por isso eles choram quando sentem fome, frio, calor, falta da mãe, tédio, fralda molhada, etc. Por isso também eles fazem cocô quando têm vontade e vomitam nas pessoas sem nenhum pudor. O lobo frontal deles vai aos poucos aprender a controlar essas coisas e se adequar ao mundo a seu redor.

aprendizado, pela capacidade de controlarmos nossas emoções e comportamentos. Bebês não sabem fazer nada disso. Por isso eles choram quando sentem fome, frio, calor, falta da mãe, tédio, fralda molhada, etc. Por isso também eles fazem cocô quando têm vontade e vomitam nas pessoas sem nenhum pudor. O lobo frontal deles vai aos poucos aprender a controlar essas coisas e se adequar ao mundo a seu redor.

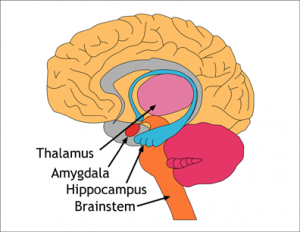

A parte inferior do cérebro, no entanto, está funcionando a todo vapor. Essa parte do cérebro:

A parte inferior do cérebro, no entanto, está funcionando a todo vapor. Essa parte do cérebro:

“contém sete forças hormonais enormes – os sistemas emocionais geneticamente arraigados. Há três sistemas de alarme – RAGE (frustração, irritação), FEAR (medo) e PANIC/GRIEF (pânico, perda, angústia da separação) – e três sistemas calmantes, de bem-estar e pro-sociais – CARE (afeto), SEEKING (procurando, desejo, antecipação) and PLAY (brincadeira, alegria, despreocupação) – e, finalmente, LUST (acasalamento). Esses sistemas são como músculos, quanto mais os ativamos, mais eles se tornam parte da personalidade”. (Sunderland, 2016, p.19)

Sem o lobo frontal desenvolvido, um bebê não tem capacidade de controlar suas emoções, que são o resultado da ativação desses sistemas hormonais. O bebê precisa de um adulto para fazer isso pra ele. Quando um bebê tem um sistema de alarme ativado (por exemplo, o sistema FEAR é ativado pela presença de uma pessoa desconhecida), ele chora descontroladamente. Quando a mãe pega o bebê no colo e o acalma, o sistema CARE é ativado, e o bebê para de chorar porque hormônios pro-sociais estão se espalhando pelo corpo dele. Conforme crescemos e o nosso lobo frontal se desenvolve, aprendemos a controlar nossas emoções com raciocínio. Digamos, por exemplo, que uma cena particularmente medonha de um filme de terror ativou o seu sistema FEAR. Rapidamente, o seu lobo frontal te lembra que é apenas um filme e o sistema PLAY é ativado, você ri de si mesmo e continua vendo o filme.

A ativação dos sistemas pro-sociais acalma, deixando-nos em um estado que beneficia o desenvolvimento do lobo frontal. Quando estamos relaxados e nos sentindo seguros, é hora do nosso cérebro aprender e do nosso organismo alocar nossas energias no desenvolvimento cerebral. Quando os sistemas de alarme são ativados – por exemplo, há um urso correndo em nossa direção – nosso corpo desvia todos os seus recursos para uma ação rápida, sem pensar muito: corre! Nessas situações a adrenalina e o cortisol (o cortisol é famoso por causar os sintomas físicos do stress, como dor muscular) são liberados e a nossa preocupação é sobreviver. Quando estamos irritados porque o trem já veio três vezes, estava muito cheio e não conseguimos entrar, e o chefe vai reclamar de novo do atraso, o mesmo sistema de alarme é ativado.

Dá para imaginar, então, a frequência com que os sistemas de alarme são ativados no brasileiro. Esperar horas na fila do banco, ser encoxada no ônibus, ser esmagado contra a porta em um metrô lotado ou ficar preso no trânsito: todas essas coisas podem ativar os sistemas de alarme, os mesmos sistemas que são ativados quando tememos por nossas vidas. A esporádica ativação não vai te matar, mas a ativação frequente tem seus perigos.

Como explica Sunderland, quanto mais esses sistemas são ativados, mais sensíveis eles se tornam. Enquanto crianças que cresceram em um ambiente seguro, com pais atentos e bastante estímulo (brincadeiras, passeios, etc) têm os seus sistemas pro-sociais constantemente ativados e se tornam adultos resilientes e confiantes, crianças que crescem em um ambiente abusivo, violento ou cheio de inconstâncias, têm seus sistemas de alarme ativados com frequência. Uma ampla quantidade de estudos indica que traumas na infância preveem uma série de problemas na vida adulta, desde ansiedade e depressão, entre outros problemas de saúde, até comportamento criminoso.

No Reino Unido, estima-se que mais de 40% da população esteja vulnerável a esses efeitos (conhecido em inglês como insecure attachment), devido a uma infância não ideal. A porcentagem é semelhante em outros países ricos. Embora não tenhamos os mesmos dados para o Brasil, é possível que essa porcentagem seja maior, e até semelhante a países em guerra, devido à alta exposição a traumas.

{Nota: quando falo de trauma, não me refiro apenas a acontecimentos que todos concordamos serem terríveis, como abuso sexual e violência física; situações muito mais sutis, como abuso psicológico prolongado, situação de dificuldade financeira e negligência podem causar danos semelhantes}

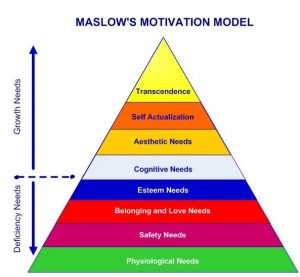

O que essas pessoas desamparadas procuram desesperadamente? Se sentir seguras. Da mesma forma que uma criança com medo procura pelos pais para receber um abraço calmante, nós adultos procuramos em outras pessoas uma forma de nos sentirmos seguros quando nosso lobo frontal não está dando conta sozinho. Para pessoas que sofreram trauma, ou que simplesmente tiveram seus sistemas de alarme ativados com muita frequência por um período de tempo prolongado, é comum confiar cegamente naquela pessoa que prometeu cuidar dela, protege-la, e se metem em um relacionamento abusivo.

O Brasil é essa pessoa, cheia de trauma e ansiedade social, entrando em um relacionamento abusivo com um cara violento que prometeu manter o país seguro. Bolsonaro é aquela droga que promete uma escapada da realidade, mas que a longo prazo vai trazer efeitos colaterais terríveis. Nós tomamos essa droga quando estamos desesperados. O Brasil está desesperado. E assim como uma pessoa que se submeteu a um relacionamento abusivo com um parceiro agressivo, não é na primeira vez que apanha que o relacionamento vai terminar. Nós deixamos acontecer de novo, e de novo, porque nos abraçamos àqueles momentos em que essa pessoa nos fez sentir seguros. Criamos desculpas para ela, ouvimos suas explicações e as aceitamos, acreditamos que é um pequeno preço a pagar para termos acesso ao lado bom dela.

E qual é a pior coisa pra dizer a essa pessoa sofrendo abuso? “Viu só! Falei pra você que ele não prestava”.

A melhor coisa a fazer: oferecer abrigo, suporte emocional, ajudar essa pessoa a se sentir segura sem o parceiro abusivo, mostrar que ela não está sozinha e ao mesmo tempo ser claro e assertivo que esse relacionamento não é saudável.

Em tempos macabros, o que o Brasil precisa é união, apoio, compreensão. A divisão de times e a segregação só vão fazer esse relacionamento durar. Vamos mostrar que o Brasil não precisa desse cara e vamos ajuda-lo a retomar sua vida. Vai ser difícil, mas o lobo frontal nos ensina que o melhor comportamento as vezes precisa de uma boa dose de autocontrole.

Referencias:

- Rifkin, J. (2009). The Empathic Civilization. New York: Penguin.

- Sunderland, M. (2016). The Science of Parenting. 2nd New York: DK.

- Sutherland, S. (2013). Irrationality. 2nd London: Pinter and Martin.

- Zeedyk, S. (2015). Sabre Tooth Tigers &Teddy Bears. Video recording, YouTube, viewed 21 Feb, 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zsAV_qez7SE&t=5932s>