Last year, a video of a seven-year-old – I`ll call him Diego – in a coastal town of Rio de Janeiro state called Macae, in Brazil, destroying the teacher`s lounge of his school became viral. In the video, the child knocks down chairs, tables, throws stuff around, makes a huge mess. The teachers stood around him, not knowing what to do. One staff, thought to be the principal, is heard making comments like: “What do we do with a child like this? Call social services, correctional office, the police?”. It was shared nearly 30 thousand times on Facebook, receiving more than 23 thousand comments, much of which were disturbing.

Last year, a video of a seven-year-old – I`ll call him Diego – in a coastal town of Rio de Janeiro state called Macae, in Brazil, destroying the teacher`s lounge of his school became viral. In the video, the child knocks down chairs, tables, throws stuff around, makes a huge mess. The teachers stood around him, not knowing what to do. One staff, thought to be the principal, is heard making comments like: “What do we do with a child like this? Call social services, correctional office, the police?”. It was shared nearly 30 thousand times on Facebook, receiving more than 23 thousand comments, much of which were disturbing.

First comment says “beat him up”; the other suggests he`s taken to a prison so the police would “freak him out”.

First comment: “lack of a beating”; second comment: “thank god my parents beat me up as a kid so today I`m not a worthless criminal or a thief, always respected everyone including my parents”. Third comment laments that, in Brazil, psychologists and human rights restrain people from providing “proper education” (?) imposing limits to children.

In the video, one of the teachers (or maybe the principal), instructs the others not to touch the boy and wait for his mother to come and pick him up. “What can we do? We are not allowed to beat him or restrain him”. No, you are not allowed. But, also, you shouldn`t (I`ll talk about that in a second). The poor boy ended up in the news, and the experts interviewed regret the teachers feel they are not allowed to impose limits to children like him.

What upsets me the most – besides the gross exposure of this child – it`s that it shows how little prepared, not only people in general (including parents and carers), but educators, psychologists and other professionals are to deal with children with challenging behaviour. And this is not exclusive to Brazil. In the UK, in 2012, “more than 40 percent of parents admitted to physically punishing or hitting a child in the past year; (…) and around 77 percent yelled at their children” (Sunderland, 2016, p.178).

I don`t blame them, though. Most parents learned they were supposed to “discipline” their children in order for them to behave. I once thought the same way, but I`ve been learning a lot since I became a parent and by working with children – and I like to share things I learn, so here we go. Here`s why children misbehave and what to do about it.

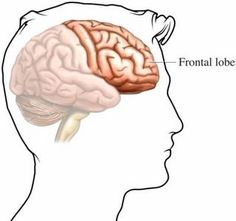

Little brains, strong emotions

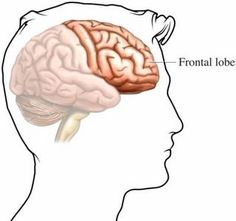

Humans are born with an underdeveloped frontal lobe, which is the part of the brain responsible for clear thoughts and intentions. This means we`re not born able to control ourselves, we have to learn it. And they usually learn through their connection with parents and cares – and also other adults around them, such as family members, educators, etc. So most misbehaving is a result of an immature brain.

In contrast with the frontal lobe, from the moment we are born, our lower brain is fully functional. This area

“contains seven huge hormonal forces – the genetically ingrained emotional systems. There are three alarm systems – RAGE, FEAR and PANIC/GRIEF – and three calm and well-being, or pro-social systems – CARE, SEEKING, and PLAY – and, finally, LUST. These systems are like muscles. The more we activate one of them, the more it becomes part of the personality”. (Sunderland, 2016, p.19)

For a child, little things like hunger or tiredness can be a reason for a tantrum, or an outburst of misbehaviour. Adults are more able to understand why they are irritated and go get some food, rest, take a walk or whatever they know will help them feel better. Children need an adult to help them cope with their feelings. What seems like a small thing for an adult can be overwhelming for a child.

When tantrums and misbehaviour are not appropriately addressed in childhood, they might continue later on in adult life. If you work in customer service, you probably know what I`m talking about.

Reasons for misbehaviour according to Sunderland (2016):

- Hunger and fatigue;

- Food (sugar, sweeteners and a number of additives can affect children`s brains);

- Undeveloped emotional brain (as previously explained);

- Understimulation of the brain (while an adult might turn the radio on, children might stimulate their own brains by causing a situation);

- Recognition hunger (children might be seeking adult attention and realises a tantrum gets a reaction);

- Need for structure (a lack of structure, like a clear routine);

- Needing help with a big feeling (tension due to a particular event in the child`s life)

- Picking up on parent`s stress;

- Wrong part of the child`s brain being activated.

This last one deserves especial attention, because it requires parents, cares and educators to change their approach. Sunderland explains that

“One of the main reasons why children behave badly is because the way a parent is relating to a child is activating the wrong part of the brain. You will have an awful time with your child if your parenting activates her lower brain RAGE, FEAR, or PANIC/GRIEF systems. You can have a delightful time if you activate her lower brain CARE (attachment), PLAY or SEEKING systems”.

Frequent yelling, physical punishment and threats will overstimulate the RAGE, FEAR, or PANIC/GRIEF systems, making the child more susceptible to bad behaviour and tantrums, and not the opposite as most people commenting on Diego`s video seem to believe.

“Next time you find yourself about to speak sharply to a child (usually for some bit of behavior you didn’t like) ask yourself if there is a gentler way you could convey your thoughts – because underneath all behavior is an emotional need, and it isn’t a need to be told off.” (Suzanne Zeedyk)

There are two types of tantrums, the distress ones and the Little Nero tantrums. They need to be taken seriously and require different responses.

Distress tantrums

“A distress tantrum means that one or more of the three alarm systems has been very strongly activated. These alarm systems are RAGE, FEAR and PANIC/GRIEF. As a result, your child`s arousal system will be way out of balance, with excessively high levels of stress chemicals searing through his body and brain”. (Sunderland, 2016, p.184)

These type of tantrums require the adult to get closer to the child, soothe her. Holding the child tenderly, offering calming words, will help her feel safe again. Then, once the child has calmed down, the best thing to do is to distract her – with a song, showing something interesting, etc.

Use your developed frontal lobe to control your emotions and deal appropriately with a challenging child.

Time-out techniques, putting a child in a room by herself or ignoring or disregarding this kind of tantrum can be harmful, possibly leading to longer, more frequent tantrums.

Little Nero tantrums

This is very different from the distress tantrums and requires the adult to react the opposite way, giving less attention to the child. This tantrum is about the desire to manipulate the adult – when a child wants sweets, for example, and tries to convince her parents to buy them by screaming and not cooperating. If the child gets what she wants, then she`s going to keep on doing it every time you say “no”.

There`s no point trying to argue, negotiate, reason or persuade the child, as that would grant her the attention she`s after. Also, don`t yell, as the child will learn this is acceptable.

Normally the child having a Little Nero tantrum will stop once ignored. Although, some children might move from a Little Nero tantrum to a distress tantrum. It`s important to distinguish them so they can be addressed correctly. If a child goes from nagging or giving you commands to a state of genuine pain, the child will then need help dealing with her feelings.

Suzanne Zeedyk reminds us, though, that “even Little Nero tantrums are still a child struggling with desire; so kindness without boundaries” is always the best approach.

When it comes to Diego, as he wasn`t demanding anything, he was quietly wrecking the room, I`d say he was having a distress tantrum. He was having to deal with really strong feeling and didn`t know how to, which resulted in the bad behaviour.

This is my personal approach to a situation like this, what I would do – though there are other ways of dealing with the situation: I`d take him (making sure I`m not hurting him in any way) somewhere, probably outside, where he can`t do much damage to property or himself. I`d use calming words such as “it`s ok; nobody is mad at you; you are ok; it will get better”, etc. I`ll wait for him to calm down and sit next to him if he lets me, maybe put my hand on his shoulder or back for reassurance. Then I`d talk to him and try to understand what triggered the tantrum. Simple questions like “how was your day” can lead to very elucidating answers on what could have winded up the child. Maybe there was a misunderstanding with other children, maybe he was bullied, maybe something is going on at home. He might not talk to me this time, or might prefer to talk about something else, or play a game. What matters it`s that the child calmed down and is now able to return to his routine.

It`s important to remember that dealing with children who often behave badly requires a lot of patience. It takes time for them to learn how to ask an adult for help and cope with their feelings. And that yelling, physical punishment, isolation and humiliation are not effective. Diego was filmed and exposed to thousands of people, many of them expressed the desire to physically punish him, and many others used unkind words to refer to him (calling him a future criminal, devil, rascal, etc). That`s collective verbal and emotional abuse of a child; one of the main causes for children and young adults to behave badly. I hope Diego is ok, but I wouldn`t be surprised if his behaviour hasn`t improved. I hope a sensible, caring adult is helping him deal with his feelings.